Chilling Prospects 2022: Ozone Treaties – a global partnership for more sustainable cooling

|

Reflections on five years of the Kigali Amendment by the Ozone Secretariat |

Cooling covers a broad segment of the economy that uses refrigerants, many of which are controlled by the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. [1] It is part of more than 200 economic sectors that include comfort cooling, cold chain for agri-food systems and vaccines, and foam manufacturing. As such, the impact from the work undertaken by Parties under the Montreal Protocol is cross-cutting and contributes to almost all Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) either directly or indirectly.

With the projected increase in global demand for cooling, [2] we need to move this sector onto a more sustainable path. Given its universal ratification and the concrete results it has achieved to date, the Montreal Protocol provides a well-established framework for transition to lower global-warming alternatives with tangible improvements in energy efficiency, safety and affordability of cooling equipment.

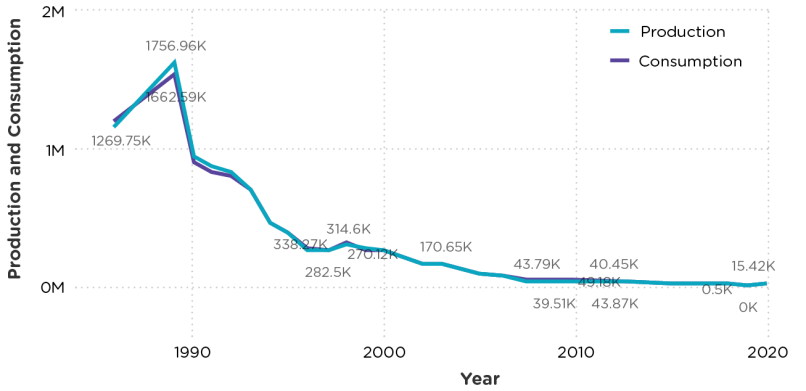

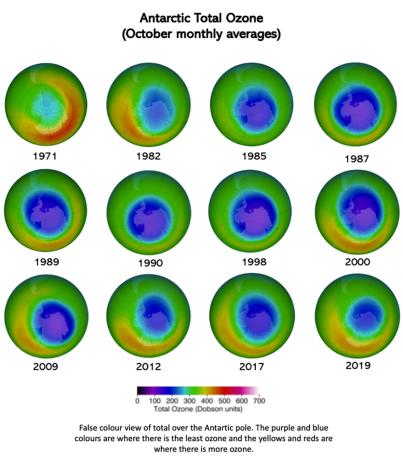

The Ozone Secretariat and the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) have developed data hubs (i.e., the data centre of the Ozone Secretariat and the World Environment Situation Room of UNEP) with interactive features for the analysis of the data reported by the Parties to the Protocol. These data show that the global implementation of the Montreal Protocol has led to the phaseout of 99 percent of ozone-depleting substances (ODS), or 1.8 million ozone depletion potential (ODP) tonnes, globally. The remaining 1 percent (approximately 200,000–300,000 metric tonnes) is largely hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs). A global phaseout of ODS is expected by 2030.

Given the high global warming potential of many ODS, it is estimated that without the Montreal Protocol atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations would have increased by an additional 115–235 parts per million by the end of the century. [3] This would have translated into a rise in global mean surface temperature of 0.5-1.0 °Celsius. In addition, the implementation of the 2016 Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, which added 18 hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) to the list of controlled substances, is projected to prevent up to 0.4 °Celsius of global warming by the end of this century. While HFCs do not destroy the ozone, they warm the climate with a potential far greater than that of carbon dioxide.