Gender-based factors in access to cooling gaps

|

Contents See also: |

The Sustainable Energy for All (SEforALL) knowledge brief Cooling for All and Gender: Towards Inclusive, Sustainable Cooling Solutions identified three main gender-related challenges that should be considered for gender-responsive cooling interventions and offers a series of recommended steps to address these challenges.

Gender-based cooling needs and heat-related risks are the results of multiple, interacting vulnerabilities. This section presents some of the observed factors related to poverty and household dynamics, health and well-being, the workplace, and decision-making that can influence the gender dimensions of access to cooling, and showcases solutions for gender-responsive approaches.

Poverty and household dynamics

- While poverty is one of the key drivers of risk, data currently available fail to reflect how women and men experience poverty within the same household. The persistent lack of sex-disaggregated data poses serious difficulties for quantifying the extent to which women and men are at high risk due to lack of cooling services.

- The interaction of poverty with other development challenges such as gender inequality, or poor access to water or sanitation facilities, hinders the ability of the most vulnerable to adapt to a warmer world.

- Women are expected to shoulder an additional work burden in the household that can exacerbate the impact of increasing temperatures and heatwaves. Food preparation, caring for children and the elderly, and water collection are not only time consuming but increasingly difficult without access to cooling services such as refrigeration, and access to safe medicines, vaccines and health services.

Gender, poverty, and economic inequalities are inherently linked [16] and influence vulnerability and adaptive capacities. However, household-level poverty data make it difficult to understand intra-household disparities and how women and men experience poverty [17] as they assume that resources are shared equally and that needs are the same for all household members. [18] Similarly, access to cooling services is expected to benefit women and men differently due to gender norms and differentiated responsibilities and decision-making roles.

A growing body of literature also analyzes other dimensions of vulnerability that contribute to limiting adaptive capacity to a warming world — including access to basic infrastructure and healthcare, the dependency ratio, food security, adult literacy rates, governance, and health status [19] — that gender-responsive cooling interventions must account for.

Different aspects and dimensions of vulnerability (regional averages of selected vulnerability indicators)

Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Link

Vulnerability to heat and adaptive capacity remain strongly linked to poverty. Understanding who the poor are and what their needs are can play a role in avoiding inequalities and reducing climate vulnerability. People in extreme poverty are more likely to live in rural areas, have more children and work in agriculture. [20]

Share and sex distribution of the poor

According to UN Women and UNDP, and the Pardee Centre for International Futures, up to 416 million women and girls and 401 million men and boys will be living in extreme poverty by 2030. 83.7 percent of the world’s extremely poor women and girls will live in two regions of the world: Sub-Saharan Africa (62.8 percent) and Central and Southern Asia (20.9 percent). [21]

Women are expected to shoulder an additional burden in the household as they are typically responsible for food preparation, caring for children and the elderly, and water collection. These activities are usually time consuming and can be exacerbated by increased heat stress. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), an estimated 76.2 percent of the total unpaid care work in 64 countries analyzed is carried out by women, equivalent to 2 billion people working full time. [22]

All household chores except house repairs are activities generally undertaken by women. [23] Girls between the ages of five and 14 spend up to 50 percent more time than boys doing household chores every day. [24] A decline in rainfall can force women to spend additional time and energy retrieving water, increasing their exposure to heat stress in high-temperature environments and reducing time for engaging in productive activities outside the household.

Ensuring access to water is crucial for reducing gender inequalities during a heatwave. As primary caregivers in many cultures, women are responsible for collecting water in eight out of ten households without running water. [25] During a heatwave, water needs within the family typically increase, exacerbating the burden of collecting it. Pregnancy also contributes to increased susceptibility to dehydration; the water needs of pregnant women increase during high temperatures. [26] Access to reliable water services can protect women from rising temperatures and allow them to dedicate more time for learning and other productive activities outside their households.

Extreme weather events are associated with additional household responsibilities for women, as well as psychological and emotional distress, reduced food intake and domestic violence. Women may experience increased domestic violence for not completing daily water-related domestic tasks. [27] Extreme heat has been associated with aggression, violent behaviour and interpersonal violence in South Africa. [28] In Los Angeles, disparities in air conditioning and greenery access have been associated with increased domestic and intimate partner violence. [29]

Health and wellbeing

- During extreme heat events, physiological and social attributes linked to gender — for instance pregnancy, type of employment or access to support networks — pose distinct challenges to the ability of both sexes to adapt and even survive. However, data remain alarmingly scarce.

- Delivering heat-resilient care, including during pregnancy and childbirth, requires prioritizing sustainable electrification of health facilities to ensure efficient refrigeration equipment to store medical products, and passive and efficient building design to ensure thermal comfort.

- The negative effects of heat stress on physical and mental well-being are exacerbated by gender disparities in access to quality housing, urban green spaces, healthcare and to safe food, and demand for gender-informed cooling interventions.

A growing body of evidence shows that rising global temperatures pose distinct risks to the health, safety and well-being of both women and men. Vulnerability to heat is associated with both physical and social attributes frequently linked to gender, leading to different patterns of mortality among genders. [30] Although women are more sensitive to heat stress, there are more registered male deaths attributed to heat stress as a result of employment both outdoors and indoors.

Recent studies show that women’s physiological vulnerability to heat can be offset by strong social support networks that men frequently lack. However, this has been seen to vary around the world. [31] For example, data from China, France and India found women and girls are more likely to die in heatwaves. [32] From a physiological standpoint, pregnancy and maternal status reduce tolerance to heat, and extreme temperatures increase the rate of adverse pregnancy outcomes. [33]

Delivering healthcare services in rising temperatures requires resilient health systems and thermal comfort in health settings. Still, an estimated 1 billion people in low- and lower-middle-income countries are served by healthcare facilities without reliable electricity. [34] This reduces the availability of lighting and cooling equipment necessary for basic maternal care and overall healthcare — including refrigerators and freezers for vaccines and medicines, and fans — and disproportionately affects women and children.

Gender inequalities also tend to adversely impact general health outcomes and access to adaptation resources. Evidence from Pakistan shows that in refugee camps, women can be at a greater risk of heat-related illness as a result of segregation in tents and having limited access to food, water and medical care. [35] Extreme weather events — including heatwaves — also appear to be associated with a greater mental health burden on women, [36] as well as an increase in violence against women, girls and LGBTQI+ people. [37]

Across the world, women are also more likely than men to experience food insecurity and associated poor health as a result of climate change. [38] This situation has worsened with the COVID-19 pandemic, and needs to be addressed with the gender-responsive deployment of sustainable and reliable cold chains. Access to refrigeration helps keep food fresh and reduce waste and has even been associated with a reduction in the risk for stomach cancer, although studies have focused largely on Western and Asian countries. [39]

Urban areas are expected to suffer more due to the combined effect of climate change and the urban heat island effect (UHIE). Gender roles and socioeconomic factors such as age and income determine the scale of impact of increasing temperatures. In urban areas, inadequate ventilation, lack of cooling shade and other passive cooling solutions are expected to increase the vulnerability of daily wage workers due to the UHIE. [40]

Women typically rely more on public transport and are more likely to travel with children or elderly relatives. [41] In the Southern Cone, one study shows that women walk more, drive and bike less and generally make more daily trips than men. [42] On longer commutes or in crowded public vehicles, women could benefit from increased attention to transit cooling solutions.

Workplace

- Agriculture can be an important engine of growth and poverty reduction, but it can also sustain poverty and reinforce gender inequality. While women represent up to 50 percent of agricultural workers, they represent only 15 percent of agricultural landholders, reflecting difficulties for women to access productive assets that could increase agricultural outputs and yields.

- Post-harvest activities are part of traditional women’s household responsibilities and often lack recognition and economic value. Cooling solutions and business models for women in post-harvest activities can open new markets for high-value crops.

- Within informal employment settings, women and men face different levels of vulnerability due to poorly built work environments and a lack of drinking water and sanitation facilities. Certain female-dominated sectors such as the garment and textile industry are calling for immediate action to protect women; male outdoor workers are increasingly exposed to high temperatures.

Agriculture

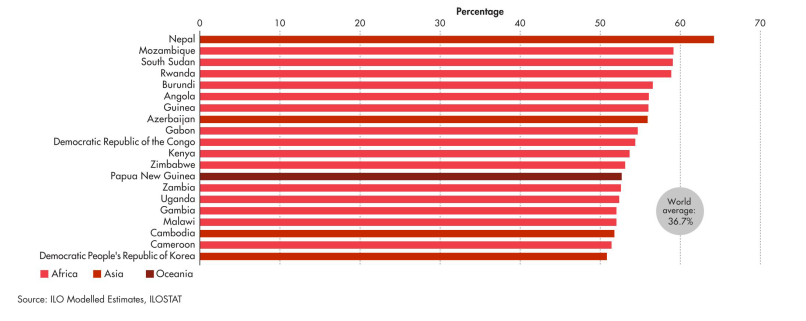

Data to assess the gendered impact of the lack of sustainable cold chains remain scarce. However, the prominent role of women in agriculture and available data on food losses sheds some light on the magnitude of the problem. The average food loss is 35 kg per person per year and losses range between 3.8 kg to 62 kg per person in the 54 high-impact countries. Globally, women represented on average 36.7 percent of all agricultural workers in 2019 but this figure can increase to more than 50 percent of the population in many African countries. [43]

Agriculture can be an important engine of growth and poverty reduction, but it can also sustain poverty and reinforce gender inequality. Roughly three quarters of extreme rural poor work primarily in agriculture. [44] Women and men in the agriculture sector tend to have different employment statuses. While both are subject to vulnerable work conditions, women are more likely to work to support their families without receiving an income. As a result of gender norms, local institutions and inadequate social protection, women represent only 15 percent of agricultural landholders. [45]

Share of women in agriculture, forestry and fishing employment, top countries (2019)

Source: World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2021

Post-harvest activities are part of traditional women’s household responsibilities and often lack recognition and economic compensation. Only 25 percent of working-age women are formally employed in the agriculture and fishing sectors. [46] Post-harvest activities include cleaning, sorting and ensuring the cooling of agricultural products after harvest to consumption.

Every year, farmers in India incur nearly USD 12,520 million in post-harvest losses due to inadequate storage facilities and a lack of energy infrastructure. This represents 25 to 35 percent of cultivated food wasted due to a lack of proper refrigeration and other supply chain bottlenecks. [47] The lack of appropriate temperature and humidity management during post-packaging, storage and transportation in low-income countries is attributed to non-existent cold chains and a lack of harvesting and processing capacity.

Food security is not only about producing enough food, but also entails access to resources and climate-resilient services, technologies and practices that ensure nutritious food in the collection, processing, distribution and consumption stages. Women play diverse key roles in food systems as farmers, entrepreneurs and as those responsible of feeding their families. Paradoxically, women have limited access to agricultural inputs, education, technology and decision-making structures and experience gender discrimination and gender violence that limit access to safe places during heatwaves — such as green spaces — and limit their mobility to sell agricultural products.

Food losses per person in high-impact countries for access to cooling

Informal and formal employment

Globally, women make up a significant number of workers in the informal sector, which often encompasses precarious and vulnerable conditions such as lower wages compared to those of men, lack of cooling and water services, and lack of toilet facilities for women. Women account for 95 percent of informal workers with respect to total employment in South Asia, 89 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa, and 59 percent in Latin America and the Caribbean. [48] Informal workers include street vendors, petty goods and service traders, subsistence farmers, seasonal workers, domestic workers and industrial outworkers.

In India, women represent 50 percent of the workforce in brick kilns where heat exposure is extreme. In informal workplaces that lack access to basic sanitation facilities, including toilets, women tend to avoid drinking water throughout the high-temperature days to avoid losing time, and with it, the risk of not reaching production quotas, or prevent sexual violence that may occur if they relieve themselves in spaces that lack privacy. [49]

Within formal employment settings, women face potentially dangerous exposure to heat in certain industries with heavy machinery and poor ventilation. Heat stress and extreme weather events not only directly impact women’s health but also decrease productivity and are associated with gender violence.

Female workers account for 80 percent of the workforce in the textile, garment and footwear industry — where they are exposed to high temperatures from machinery — but only 5 percent of factory supervisors are female. [50] 75 percent of the industry is based in the Asia-Pacific region. When temperatures surpass 29°C in garment factories in India, productivity is expected to decrease by 3°C for each degree increase. [51] In hot and poorly ventilated garment factories, a decrease in productivity has been associated with gender violence. The effectiveness of fans in such contexts remains uncertain while inefficient air conditioners can increase energy consumption and reduce profits.

Next

Call to actionNotes and references

[16] Families in a Changing World: Progress of the World’s Women 2019-2020. UN Women. Link

[17] Gender differences in poverty and household composition through the life-cycle: a global perspective. World Bank, 2018. Link

[18] Inside the Household: Poor Children, Women and Men. World Bank, 2018. Link

[19] Regional clusters of vulnerability show the need for transboundary cooperation. Joern Birkmann et al 2021. Link

[20] Critical 9 refers to the top nine high-impact countries for access to cooling. They are: Bangladesh, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan and Sudan.

[21] Poverty deepens for women and girls, according to latest projections. UN Women. Accessed in 2023. Link

[22] Care Work and Care Jobs For the Future of Decent Work. ILO, 2018. Link

[23] Idem

[24] Harnessing the power of data for girls. Taking stock and looking ahead to 2030. UNICEF, 2016. Link

[25] State of the World’s Drinking Water: an urgent call to action to accelerate progress on ensuring safe drinking water for all. WHO, 2022.Link

[26] Samuels, L., Nakstad, B., Roos, N. et al. Physiological mechanisms of the impact of heat during pregnancy and the clinical implications: review of the evidence from an expert group meeting. Int J Biometeorol 66, 1505–1513 (2022). Link

[27] Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC 2014. Link

[28] The archaeology of climate change: The case for cultural diversity. Burke et al, 2021. Link

[29] Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC 2022. Link

[30] Heat stress and public health: a critical review. Kovats, R. and S. Hajat, 2008. Link

[31] Vulnerability to heat-related mortality in Latin America: a case-crossover study in São Paulo, Brazil, Santiago, Chile and Mexico City, Mexico. Link

[32] Gender and Climate Change: A Closer Look at Existing Evidence. Global Gender Climate Alliance, 2016. Link

[33] Health, Wellbeing, and the Changing Structure of Communities. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, 2022. Link

[34] Energizing health: accelerating electricity access in health-care facilities. Geneva: World Health Organization, the World Bank, Sustainable Energy for All and the International Renewable Energy Agency; 2023. Link

[35] Pakistan's refugees face uncertain future. The Lancet, 2009. Link

[36] Climate Inequality Report 2023. World Inequality Lab Study, 2023. Link

[37] Health, Wellbeing, and the Changing Structure of Communities. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, 2022. Link

[38] SDG2 Indicators. FAO, accessed 2022. Link

[39] Association between refrigerator use and the risk of gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One. 2018. Link

[40] Climate change and urban children: impacts and implications for adaptation in low- and middle-income countries. Bartlett et al., 2008. Link

[41] All too often in transport, women are an afterthought. World Bank, 2022. Link

[42] Closing Gender Gaps in the Southern Cone: An Untapped Potential for Growth. IaDB, 2022. Link

[43] World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2021. FAO, 2021. Link

[44] Ending extreme poverty in rural areas – Sustaining livelihoods to leave no one behind. Rome, FAO. Link

[45] Restricted access to productive and financial resources. OECD, 2019. Link

[46] Employment indicators 2000–2019. FAO, 2019. Link

[47] Chilling Prospects 2022. SEforALL, 2022. Link

[48] Women in Informal Economy. UN Women. Accessed in 2023. Link

[49] Heat stress and inadequate toilet access at workplaces in India – a potential hazard to working women in a changing climate. Climanosco Research Articles, 2019. Link

[50] Turning up the heat: Exploring potential links between climate change and gender-based violence and harassment in the garment sector. ILO, 2021. Link

[51] Idem