Global access to cooling in 2021

|

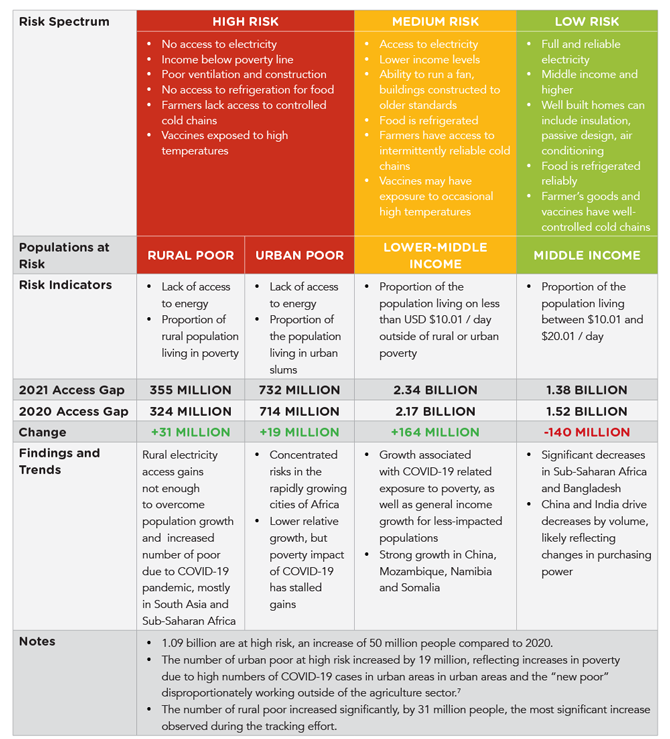

The analysis for 2021 shows that across 54 high-impact countries identified in previous Chilling Prospects reports, 1.09 billion people among the rural and urban poor are at high risk due to a lack of access to cooling. A further 2.34 billion lower-middle income people pose a different kind of risk: they will soon be able to purchase the most affordable air conditioner or refrigerator, but price sensitivity and limited purchasing options mean they favour devices that are likely to be inefficient, threatening energy systems and resulting in increased GHG emissions. |

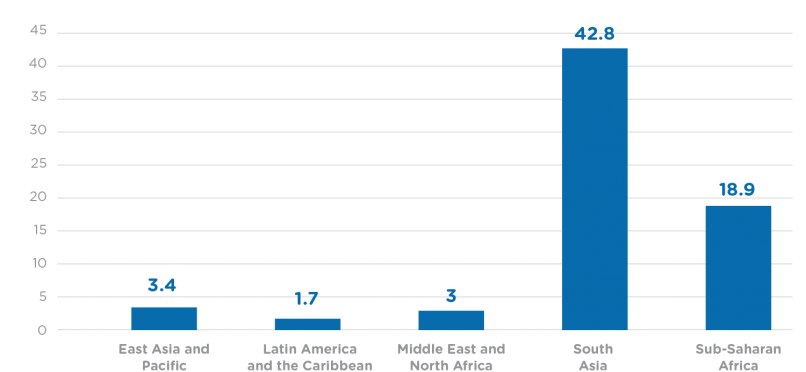

In 2020, global development efforts stalled as governments worked to address the health, social and economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. For the first time in 20 years, global poverty is set to increase, with between 119 and 124 million people globally being forced into extreme poverty due to the pandemic. Approximately 60 percent of the increase will be among people living in South Asia and 27 percent among those living in Sub-Saharan Africa. In 2021, that figure is projected to rise to between 143 and 163 million. [1]

At the same time, 2020 tied with 2016 as the hottest year on record. [2] Heatwaves were documented in North America and Australia, and summer temperatures as high as 38°C in the Siberian region of Russia catalyzed wildfires that emitted record amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) and raised fresh concerns about the global warming impact of rapidly melting permafrost in the region. [3]

New academic efforts also brought attention to the fact that heatwaves and their impacts are likely under-reported in Sub-Saharan Africa [4] and that in every region of the world, heatwaves have increased in their frequency and length since the 1950s. [5]

The combination of these two factors — COVID-19 and increased temperatures — coupled with persistent energy access gaps in some of the world’s hottest and most populous countries, means that the challenge of delivering access to sustainable cooling is likely to continue to grow in size and scope, though changing in its dimensions as people migrate to cities and countries Recover Better from the pandemic.

Compared to 2020, the analysis shows an increase of approximately 50 million people who are at high risk of a lack of access to cooling. The number of urban poor at high risk has grown by approximately 19 million from 714 to 732 million, [6] while the rural population has grown by 31 million from 324 million to 355 million. The lower-middle income population increased from 2.17 billion in 2020 to 2.34 billion in 2021. Across the 54 high-impact countries, at least 3.43 billion people still face cooling access challenges, with global risks amplified by an additional 50 million people at high risk in 2021.

Table 1.1: Analysis of risk from a lack of access to cooling

The poverty impact of COVID-19

The poverty impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on increased access to cooling risks is clear. Forecasts from the World Bank, IMF and other international institutions show that just under 70 million people in the 54 high-impact countries for access to cooling were forced into extreme poverty in 2020 as a direct result of the pandemic. While this was likely counteracted by preexisting access to electricity and established housing, the economic impact of the pandemic had cascading household impacts. Social distancing measures have had an impact on jobs and the ability to seek communal cooling resources. Faced with a decline in incomes, for example, households likely prioritized more basic or affordable services, for example favouring cereals or grains that provide higher caloric value per dollar, but do not require refrigeration. [7]

Governments similarly prioritized direct stimulus payments and employment supports, and despite women facing the most significant of the economic impacts of the pandemic, only 13 percent of the COVID-19 fiscal, social protection, and labour market measures targeted the economic security of women as of March 2021. [8]

Impacts were felt significantly in Asia and the Middle East, where 28 million additional people are at high risk, and Africa, where 19.4 million additional people are at high risk, consistent with the forecasts showing South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa to be the regions with the largest numbers of people forced into poverty due to the pandemic. Ongoing urbanization, particularly in the fast-growing cities of Africa, as well as rural population growth in both regions also contributed to the relative increases. These access gaps are in addition to those who may face temporary difficulties accessing a COVID-19 vaccine specifically as a result of a lack of rural cold chain infrastructure (see Chapter 3).

As the pandemic continues, access to cooling will play a vital role in the global economic recovery from it. From the cold chains that carry vaccines to rural health clinics, to the jobs a connected agricultural sector supports, sustainable cooling solutions are vital to Recover Better with Sustainable Energy. [9]

As governments work to Recover Better by implementing policies that support sustainable cooling, the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7) and poverty reduction, access to sustainable cooling can be expected to increase. While the pace of these economic recoveries is likely to differ, over time they can be expected to reduce the number of those at highest risk due to a lack of access to cooling, including the temporary access gaps caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1.1: Estimated increase of absolute poverty in 54 Chilling Prospects priority countries by region (millions)

Notes and references

1 Lakner, Christoph, et al. “Updated estimates of the impact of COVID-19 on global poverty: Looking back at 2020 and the outlook for 2021,” World Bank Group, 11 January 2021. Link

2 “2020 Tied for Warmest Year on Record, NASA Analysis Shows,” NASA. 14 January 2021. Link

3 Stone, Madeline, “A heat wave thawed Siberia’s tundra. Now, it’s on fire,” National Geographic, 6 July 2020. Link

4 Harrington, Luke and Friederike Otto, “Reconciling theory with the reality of African heatwaves,” Nature Climate Change 10, 13 July 2020. Link

5 Perkins-Kilpatrick and S.C. Lewis, “Increasing trends in regional heatwaves,” Nature Communications, 11, 3 July 2020. Link

6 Note: figures may not add up due to rounding. The number of urban poor at high risk has grown from 713.5 million to 732.3 million, a difference of 18.8 million.

7 Headey, Derek D and Harold H Alderman, “The Relative Caloric Prices of Healthy and Unhealthy Foods Differ Systematically across Income Levels and Continents,” The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 149, Issue 11, November 2019. Link

8 Women’s absence from COVID-19 task forces will perpetuate gender divide, says UNDP, UN Women, UN Women, March 22, 2021. Link

9 Recover Better with Sustainable Energy, Sustainable Energy for All, 2020