Chilling Prospects Data Story: Cooling Access Risks in High-Income Countries

The Chilling Prospects research series focuses on cooling access risks faced in high temperature areas of the Global South. However, it is increasingly evident that extreme heat and vulnerability due to a lack of access to cooling is affecting wealthy, developed countries, and costs are paid in productivity and lives lost. Vulnerabilities are proving to be similar, regardless of developmental stage. Across 854 cities in Europe, a June-July heatwave killed over 24,400 people, 85% of which were over the age of 65. Construction practices that prioritized sheet metal roofs exacerbate the impacts of heatwaves in Paris, and during a heatwave in Vancouver the poor suffered the most, with deaths among materially and socially deprived people almost doubling.

Access to cooling risks in high temperature areas of the Global South arise due to energy access gaps, poverty, poor housing quality, gender, and age, among other factors. While developed countries typically have sufficient energy infrastructure access to power cooling solutions, most other risk factors are similar those in developing and emerging economies, and can create serious cooling access risks. For instance, the impacts of extreme heat are also felt disproportionally by those suffering from relative poverty or at economic disadvantage regardless of geography. Other shared risk factors include age (infants and the elderly), gender, and those with health conditions that make them susceptible. These risks typically arise in developed economies during heat extremes where temperatures are significantly in excess of seasonal averages, and because of specific compounding circumstances that include a lack of public preparedness, inadequate housing and building standards, and lower physiological tolerance of heat.

Across 854 cities in Europe, a June-July heatwave killed over 24,400 people, 85% of which were over the age of 65.

Poverty drives cooling access risks in the Global North similarly to the Global South. In the United States for example, over 90% of households have an air conditioner, but heat-related mortality risks are higher for those in poverty, who may not be able to afford an air conditioner and who live in urban areas without green and blue spaces.[1] Between 2018 and 2022, heat stress death rates in New York City were highest in neighborhoods where more than 30% of residents live below the poverty line. Low-income Americans, as well as those living in minority communities typically experience higher temperatures in the summer months,[2] conditions that may be exacerbated by low quality housing, a lack of green and blue spaces to absorb heat, and energy poverty, where households may not be able to afford or power a cooling device.

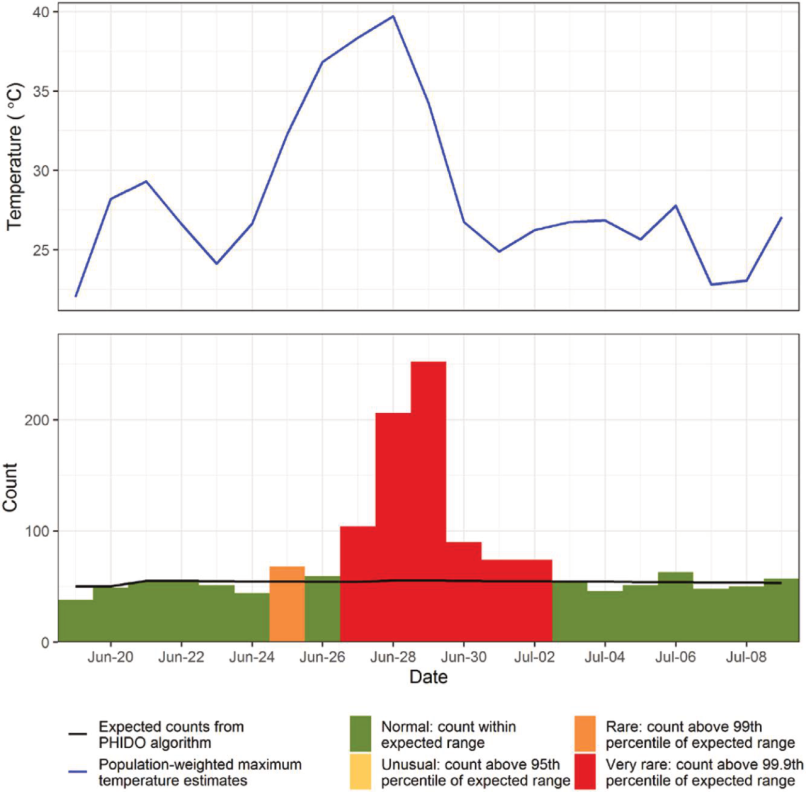

Those above the age of 65 are at particular risk of mortality, a challenge made evident by the 2025 European heatwave. Their risk factors include higher relative rates of heart, kidney, or lung disease, which are exacerbated in high temperatures, reduced thermoregulation, and social isolation. A rapid assessment of the 2025 European heatwaves found that high temperatures killed 24,405 people across 854 cities between June 23rd and July 2nd. During this period, temperatures exceeded 46°C in both Portugal and Spain and Southern Italy saw temperatures exceed 40°C, where a four-year old boy died of heatstroke. Of the deaths in the cities assessed, however, over 85% of the victims were estimated to be above the age of 65.[3]

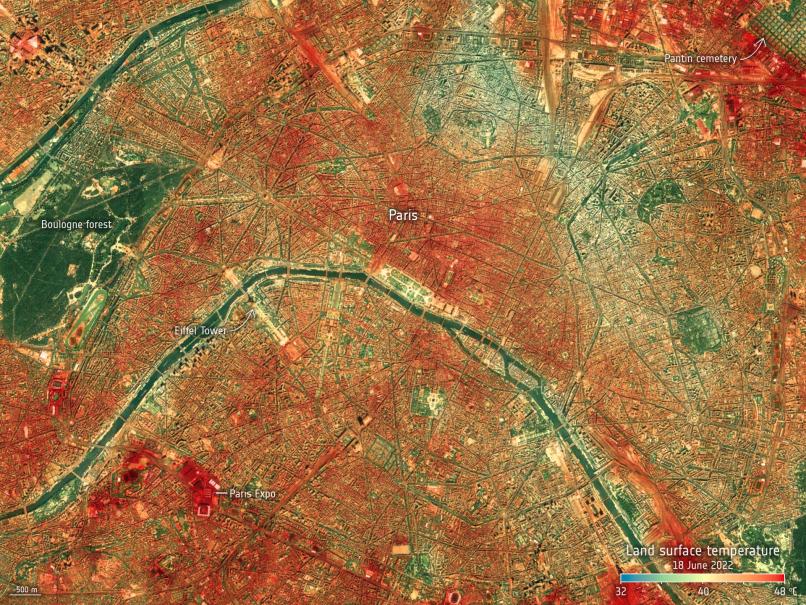

The 2025 heatwave in Europe also exposed the challenges faced by European urban centers designed for colder climate when heat stress arises. In Paris, where heatwaves have also proven deadly in 2003, 2019, and 2022, over 60% of roofs are made from sheet metal, typically zinc, a feature of the Haussman architectural style popular in the city in the mid-19th century. Similar to the sheet metal used in poor urban slums in developing countries, Paris’ zinc roofs absorb heat and temperatures above them can reach up to 16°C higher than ambient air temperature, contributing significantly to the urban heat island effect. Top floor apartments underneath these roofs can reach up to 70°C. At the same time, only 10% of the city is made up of green space and it is estimated that only 22% of French households use air conditioning. A study from the Lancet found that among European capitals, Paris is the most dangerous city for mortality from extreme heat, with 1.6 times greater risk than its counterparts.

People living in cooler, temperate climates are typically socially and physiologically unprepared for extreme heat events that are becoming more common with climate change. On such example is the ‘Heat Dome’ that affected Vancouver, Canada from June 27 to July 2, 2021, where summer temperatures rarely exceed 30°C. During this period, sustained, high atmospheric pressure trapped warm air over the Pacific Northwest and forced it downwards, causing the heat dome. Historically, mean 3-day maximum temperatures in the city during this period averaged 23°C, and as a result most dwellings do not need air conditioning, and residents do are not physiologically adapted for high temperatures. During the heat dome however, the mean 3-day maximum temperature was 36.3°C, with peak highs of over 40°C. Subsequent analysis of the heat event determined that 434 people died due to extreme heat during the event, a 440% increase in mortality compared to typical weather. The effects were felt disproportionately by women and the poor. Among those that died, 54.6% were female, compared to 43.3% of deaths during typical weather, and 28.1% were materially and socially deprived, compared to 14.9% during typical weather.[4]

The rise in extreme heat events, and the associated consequences for mortality in developed countries is making it clear that access to cooling risks are not limited to developing and emerging countries in hot climates. While these countries may not grapple with energy access challenges, similar risk factors such as energy poverty, low socio-economic status, gender, and building construction practices tailored for colder climates, drive exposure to heat related mortality in these countries. This makes it clear that protecting vulnerable groups from the effects of extreme heat is, and will continue to be, a shared challenge globally – one that requires collaboration, knowledge exchange, and shared best practices to tackle.

Read more about the risks faced by countries in the Global South due to a lack of access to cooling.

[1] Xu, J., Fan, C., Su, X. et al. An inference approach for assessing place-based vulnerability to heat mortality. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1324 (2025). Link.

[2] Benz, S. A., & Burney, J. A. (2021). Widespread race and class disparities in surface urban heat extremes across the United States. Earth's Future, 9, e2021. Link.

[3] Clarke, B., et al. (2025). Climate change tripled heat-related deaths in early summer European heatwave. Grantham Institute report. Link.

[4] Henderson SB, McLean KE, Lee MJ, Kosatsky T. Analysis of community deaths during the catastrophic 2021 heat dome: Early evidence to inform the public health response during subsequent events in greater Vancouver, Canada. Environ Epidemiol. 2022. Link.